USDA Cuts a Rule, Plans a Road, but May Not Reap a Harvest: The Disappearance of the “Roadless Rule”

By Ryan Luvera, Aquatics and Fisheries Sciences, Marine Biology ‘26

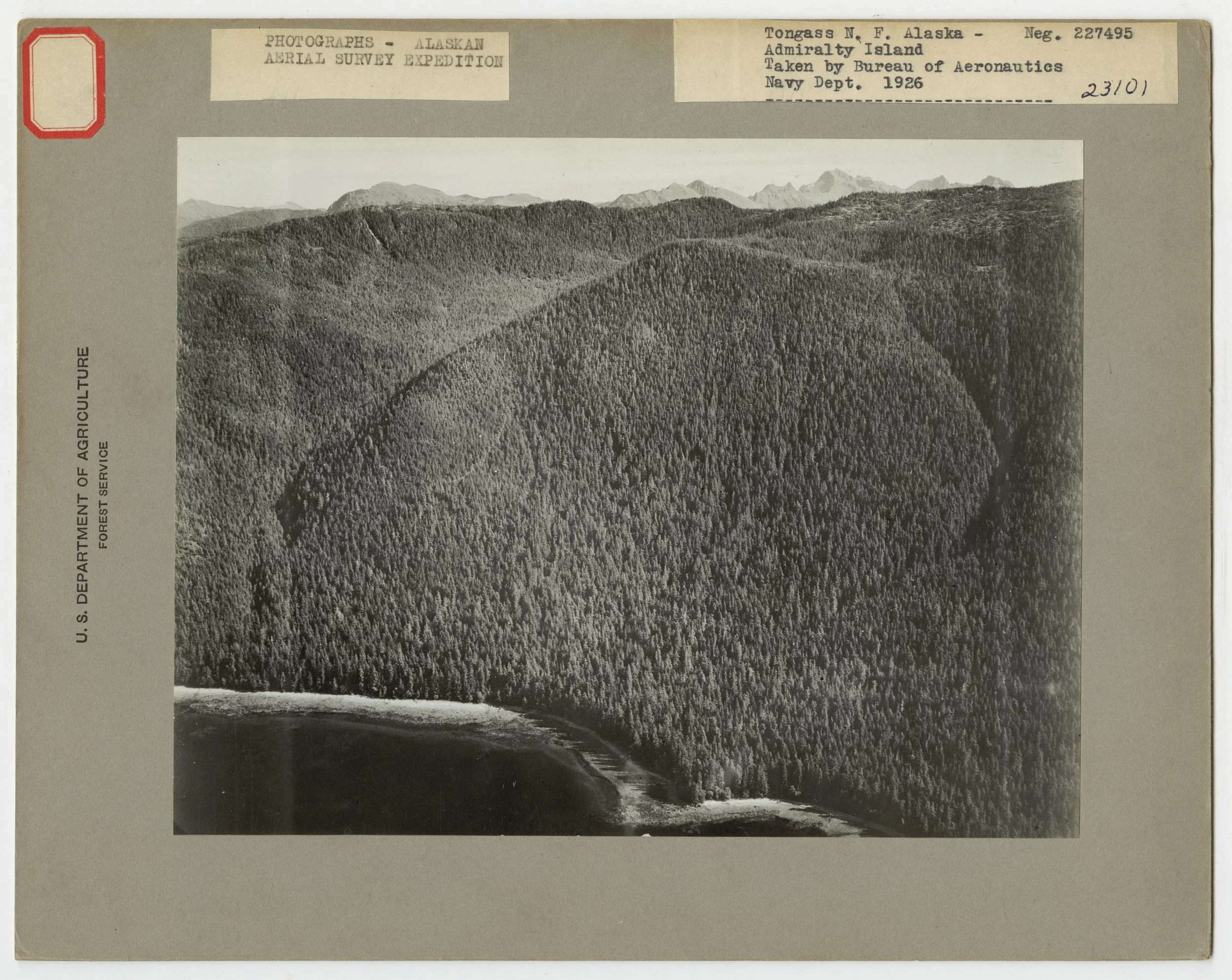

Aerial survey of Tongass National Forest, Juneau, Alaska (1926). Photo by USDA.

Roads often seem benevolent. We use them to bring goods from city to city, visit relatives across the country, and cross mountains in mere hours. But building a road is a permanent decision that is rarely reversed.

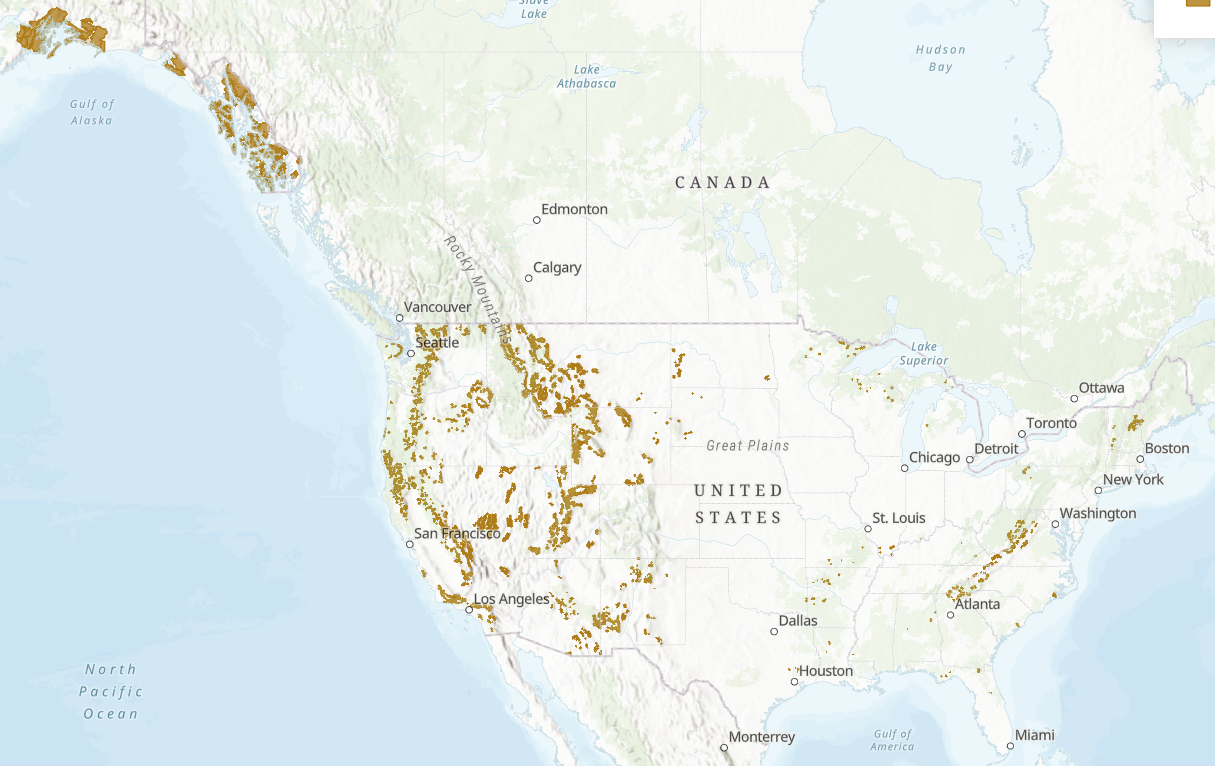

The “Roadless Rule” was enacted to protect portions of our national forests from further development. Enacted in 2001, the Roadless Rule protected 58.5 million acres of forest land––the size of the state of Washington and West Virginia put together–from development of road networks vital for both logging and mining interests.

In total, 30% of US national forests were barred from development, but still accessible via maintained trails for camping, skiing, hiking, and public access. This rule was met with huge public support, garnering 1.6 million public comments in 2001, the most ever in US history at the time, with 95% in support of the rule. Aiming to keep rivers clean, provide habitat for wild animals, the rule was ultimately a “down payment on the well-being of future generations” as former Forest Service Chief Mike Dombeck put it.

2001 inventoried roadless areas in the US, excluding Puerto Rico. Photo by ESRI, USGS, USFS.

As the largest national forest in the US, the Tongass forest in Alaska started logging with the main goal of bolstering rural economies and supporting domestic development. To support this goal, taxpayers have paid an estimated $1 billion dollars since 1982 to keep Tongass logging afloat, all while the industry has shrunk. This investment has been met with resistance as an average of 92% of the industries revenue has been from whole log exports to Asia, eliminating sawmill and processing plant jobs in the US.

With the Roadless Rule suppressing large-scale commercial logging in the Tongass, local grassroots support for logging is gaining traction. The Sitka Conservation Society has focused on building community around logging, integrating local school projects with locally sourced wood. “For us at the Conservation Society, doing things in that way makes a lot more sense and is a lot more sustainable than loading up all of our logs onto a ship and sending them to China,” executive director Andrew Thoms said. Thoms continues that the Roadless Rule rescission is “a huge distraction that’s taken energy and time away from doing the kind of project that we need to do to move things ahead.”

But for the rest of the US, fire suppression and economic inhibition are the main drivers against the rule. “If you can’t build a road, you can’t fight fires, you can’t cut trees, and you can’t properly take care of our national heritage held in our public lands.” said Congressman Ryan Zinke, R-Mont. The rule has also been argued to hinder rural communities ability to “harvest timber, develop minerals, connect communities, or build energy projects at lower costs—including renewable energy projects like hydropower” , said Senator Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska.

But the US Forest Service will face some difficulty in paving new roads. With a current $5 billion dollar deficit for road construction and maintenance, there is already a heavy backlog. New road construction will be difficult without a significant investment into the logging industry across America.

The fate of the Roadless Rule still remains partly in the hands of the public, with the next comment period set for March 2026—an opportunity for America to shape what comes next.