The Buzz About Colony Collapse: What's Killing Washington's Honeybees?

By Lily Peterson, Marine Biology ‘25

Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) is a beekeeper's nightmare. Millions of honey bees missing from their hives, larval honeybees left without food, and queen bees spared only to suffer without their colony. It is a mysterious murder scene that no beekeeper wants to witness. This phenomenon, first identified in the United States in 2006, has since spread to other Northern Hemisphere countries.

As a keystone species, honeybees play a critical role in the ecosystem; their decline can disrupt ecological balance and impact both other species and humans. Before commercial beekeeping began in the 1800s, pollination was exclusively performed by honeybees from naturally occurring hives. Many farmers now rely on commercial beekeeping, as pesticides have decimated most wild bee colonies worldwide. Pesticides have been proven to harm the health of commercial hives as well. Today, the U.S. allows neonicotinoid pesticides, which can inflict contamination-induced death on honeybees, cause changes in migratory behavior, and lead to mass die-offs during pollination events.

Near the end of the 19th century, commercial and natural hives began to experience nutritional stress due to a decrease in available flowering plants and land. Near the end of the 20th century, parasites and pathogens began infiltrating bee colonies in the U.S. In 1987, a parasite called the Varroa mite arrived in U.S. hives and has since been identified as the most common perpetrator involved in CCD. These mites suck the hemolymph–the bee version of blood–from the bodies of honeybees and transmit pathogens, such as deformed wing virus, in the process. Shive beetles, native to sub-Saharan Africa, were first found in the U.S. in 1996 and spread to 30 states by 2014. It has also been discovered that the average lifespan of the Northwest honeybee has declined since the 1970s due to global warming. A research study at Washington State University, conducted using climate and bee population models, revealed that with an increase in the autumn season length leading to late-season flight, the age structure of the colony is skewed.

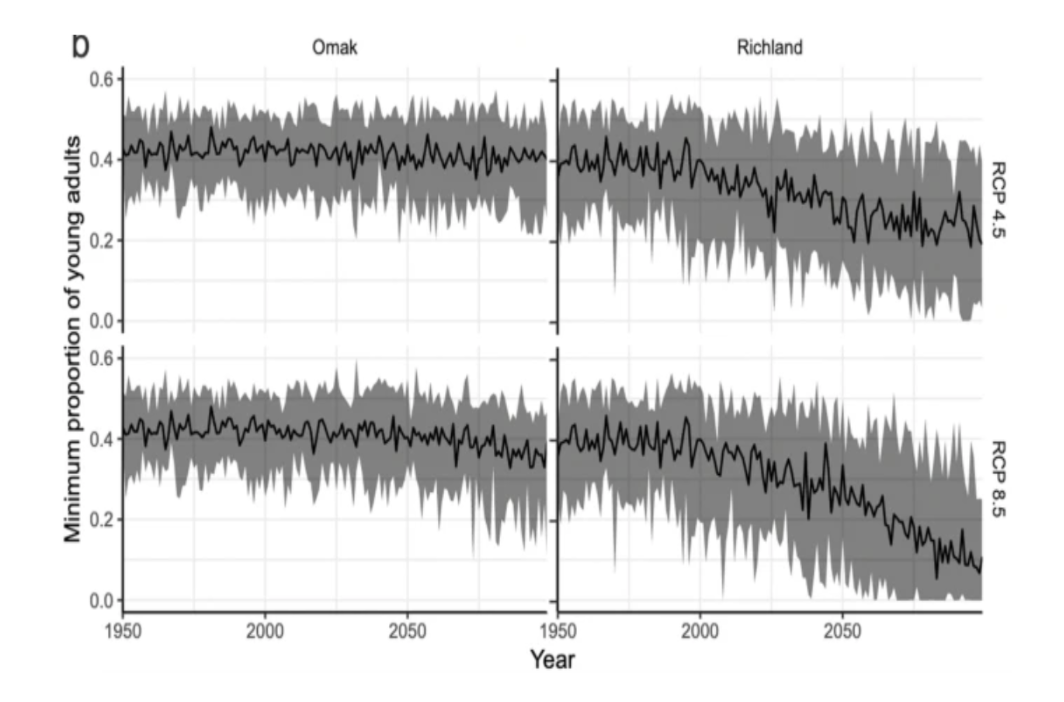

Time series plots from the WSU study showing the decrease in the proportion of young adult honeybees in both testing locations involved. The data is modeled from 1950 to 2099 (Image Credit: Rajagopalan et al., 2024).

WSU researcher Brandon Hopkins labeling honeybee hives inside a cold storage facility in January 2021 (Image Credit: Brandon Hopkins).

The data revealed that changes in age structure lead to a greater risk of colony loss in spring. This places responsibility on global warming as a primary suspect in the large-scale deaths of honeybees observed in CCD cases. However, the WSU study only controlled for the effects of climate change itself on CCD, despite previous data suggesting that climate change may not be acting alone. Likely, accomplices like pesticides and parasites are also actively contributing to the demise of these hives. Since 2006, scientists have identified parasites, pathogens, pesticides, handling, and environmental change as possible perpetrators. However, further research is necessary to distinguish the primary threat to honeybees. Fortunately, state legislature and individual farmers have responded by taking action to combat various threats. This has included the passing of important measures in bee-friendly landscaping, the utilization of cold storage in beekeeping, and the delivery of native plant habitat kits to problem areas.